You can find the whole piece in Culinary Chronicles, Occasional Papers of the Culinary Historians of Canada, New Series, Issue 4, Fall 2024, here; the issue costs CAD $10.

Hamilton’s First Cookbook Excerpt

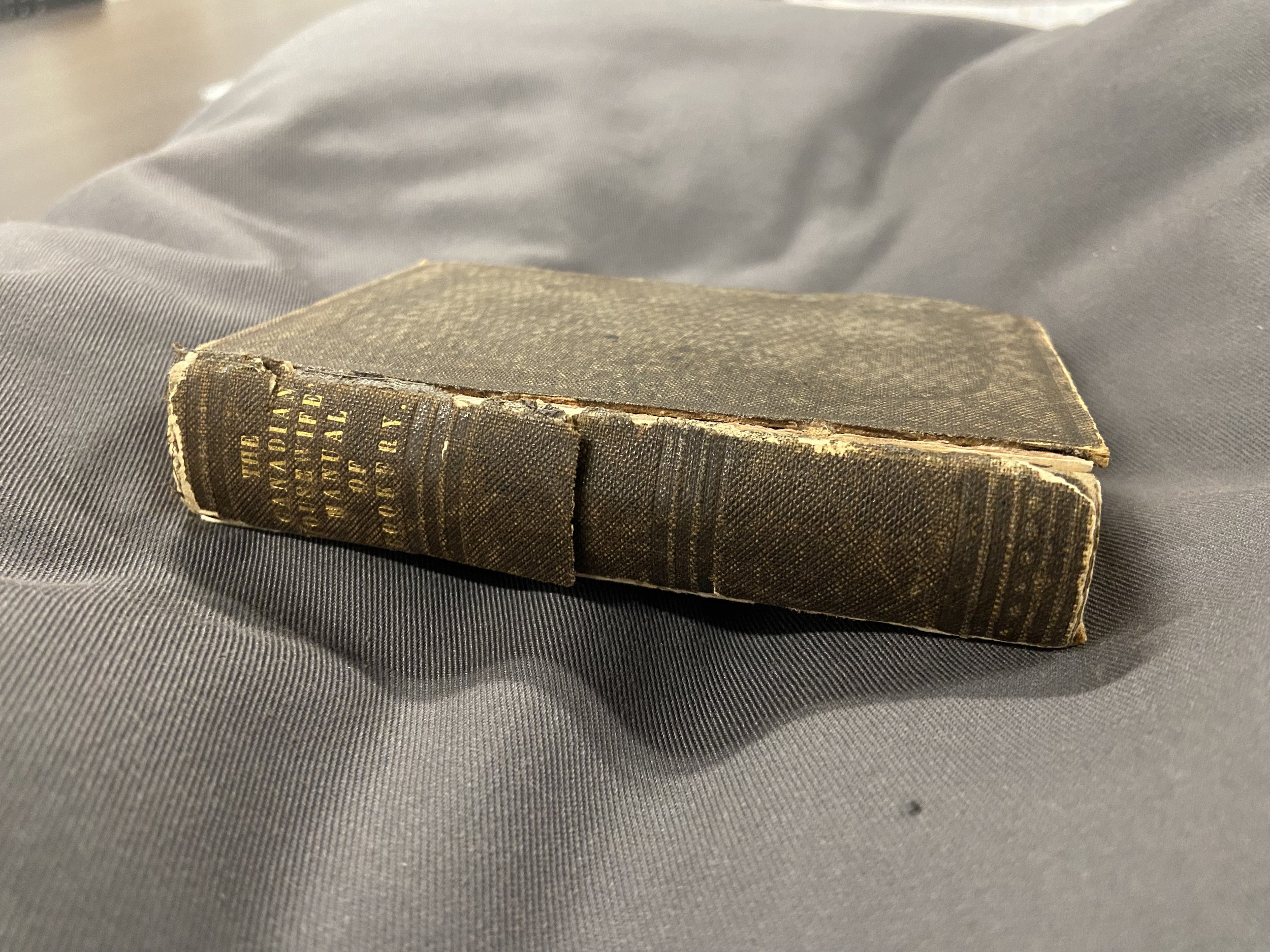

Front cover and spine. The Canadian Housewife’s Manual of Cookery, University of Guelph.

Henry and Elizabeth, Part 1

In 1861, the year The Canadian Housewife’s Manual was published, Hamilton was a busy industrial centre on the verge of a comeback after a depression in 1857.25 It was the second largest city in Canada West (Ontario) at 19,000 people, compared with Toronto’s 45,000.26 The population comprised mostly Irish, Scottish, and English people, but also included smaller numbers of other nationalities, and Canadian-born and Black people.27

Henry and Elizabeth Richards lived in a two-storey wood frame house at Main and Walnut Street.28 They’d been in Hamilton for less than a decade; Henry doesn’t appear in Hamilton city directories until 1856. He was a printer by trade, an occupation that saw him setting type and printing for The Hamilton Spectator jobbing department in Prince’s Square.

The Richards were Wesleyan Methodists, one of the more affluent groups in the city.29 They were both 45 years old. Elizabeth was from Hampshire and Henry from Guernsey, England.30 They’d had a daughter in 1857.31 Henry was a highly visible resident of Hamilton,32 who appeared in the news- papers many times, mostly connected to his work, but for other reasons too. He was a member of the St George’s Society33 and treasurer for their church’s sabbath school.34 He was a signatory to a letter in support of prominent citizen Isaac Buchanan’s political ambitions.35 And he won second place for the best pair of rabbits in the 1860 Provincial Agricultural Exhibition.36

They employed a live-in servant, Sarah, a sixteen-year-old English girl, making them part of the one-quarter of Hamilton households that could afford to hire servants. They had three boarders – Francis and Robert Huston, two Irish brothers who worked as brushmakers, and Rosanna Foster, a widowed nurse. This is another indication of economic stability, since boarders were more common in affluent households; the houses were bigger.37

As I collected information about Henry and Elizabeth, the more I wanted to know. My quest to understand the food culture of mid-19th century Hamilton had evolved into a desire to learn more about this cookbook and its authors, and the context and city from which it and I came.

Henry at Work

Henry worked at the Spectator printing office on Main Street between James and Hughson. At that time, it was still called The Hamilton Spectator and Journal of Commerce.38

As a printer, Henry set type by hand, all while breathing in strong vapours from ink, lye, and wet paper. In dim light from kerosene lamps, he used a cylinder press powered by steam, newly available technology that made it possible to publish newspapers on a daily basis. After the paper was printed in the morning, the office could take on print jobs (hence “jobbing” department) like stationery and books.39

Figure 4. The Hamilton Spectator office, 1868–69 Sutherlands Hamilton City Directory, 47.

Printing offices were often combined with a bookstore, stationery shop, or bindery, and were al- most always connected to a newspaper, within which they advertised their own services. An advertisement frequently appeared on the front page of the Spectator in 1861 that boasted of “Every description of plain and fancy printing executed at the ‘Spectator’ steam printing office.”40 It is possible that this very advertisement was set by Henry, whose Spectator career spanned from the early 1850s to late 1860s.41

His connection with the Spectator and job printing department was how he was positioned to publish and advertise the Manual. He ran at least seven pre-publication advertisements in the Hamilton Spectator, two of which also solicited advertisers for the 2,100 copies he intended to print. The book was described as “Cloth, Gilt Lettered – price 75 cents.” After publication, the ad ran nine more times, until winter 1862, with a revised price of 50 cents.42

Elizabeth at Work

As a housewife, Elizabeth was responsible for running the household. She was the target for the proliferation of books coming from Britain and the United States describing how to behave and run a household, the best known being Isabella Beeton’s Book of House- hold Management, published in 1861, the same year as the Manual. Like today, books on household management were aspirational, even competitive.

In her diary, a woman named Matilda Bowers Eby expressed the need for guidelines for housewives:

I am sorry so many of our Canadian girls don’t learn to keep house thoroughly and try to make themselves worthy of the position they all aspire to occupy in the community some day. How often we see that worthless and extravagant wives are the ruin of their husbands. When will women wake up to their duty? It would not be a bad thing if some intelligent woman would write a little work entitled ‘Women’s duties’ and circulate it through our lovely Canadas.43

Matilda’s request was answered, somewhat, by Henry, though he wasn’t a writer or intelligent woman himself. In fact, the Introductory Observations for the Use of the Mistress of a Family were plagiarized from Rundell’s A New System of Domestic Cookery, like so many of her recipes. But they echoed Matilda’s sentiments: “There was a time when ladies knew nothing beyond their own family concerns; but, in the present day, there are many who know nothing about them; each of these extremes should be avoided.” Housewives were urged to “make the home the sweet refuge of a husband fatigued by intercourse with a jarring world: to be his enlightened companion and the chosen friend of his heart: these are woman’s duties, and delightful ones they are.”44

While some women embraced keeping house, others quietly complained in their diaries, like Emma Laflamme: “I should not like housekeeping, i.e. the sole charge of it for more than three or four weeks at a time. It is astonishing how much time it takes up.”45 Others complained loudly, like journalist Kathleen Blake Coleman in the Toronto Mail:

It is difficult, isn’t it, to get up something different, and yet dainty and not too ex- pensive for breakfast, dinner and luncheon every day? This everlasting cookery be- comes very burdensome to the house- keeper after a while, and in fact I have known more than one little woman to sit down and have a good cry over the dif- ficulty of providing something nice and different every day.46

You can find the whole piece in Culinary Chronicles, Occasional Papers of the Culinary Historians of Canada, New Series, Issue 4, Fall 2024, here; the issue costs CAD $10.